This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s ports

In the course of my life I have probably spent, without exaggeration, at least 1,000 hours in Buenos Aires drinking coffee and listening to people offer their pet theories on how Argentina lost its way.

Throughout those conversations, I’ve heard friends and politicians variously blame: Juan Perón, Eva Perón, Isabel Perón, Old Juan Perón (less enlightened with the years, some insist); the anti-Peronists, the “gorillas,” the milicos; the markets, the unions, the farmers; neoliberalism, communism, fascism, capitalism; Néstor and Cristina Kirchner, Cristina but not Néstor, the anti-Kirchnerists, the vulture funds; the One World government, the São Paulo Forum, the Cuban intelligence services, the U.S. intelligence services, and the Washington Consensus. This is only a partial list.

I eventually arrived at the conclusion that it’s all of these things, and none of these things. Indeed, Argentina’s biggest challenge today is probably history itself.

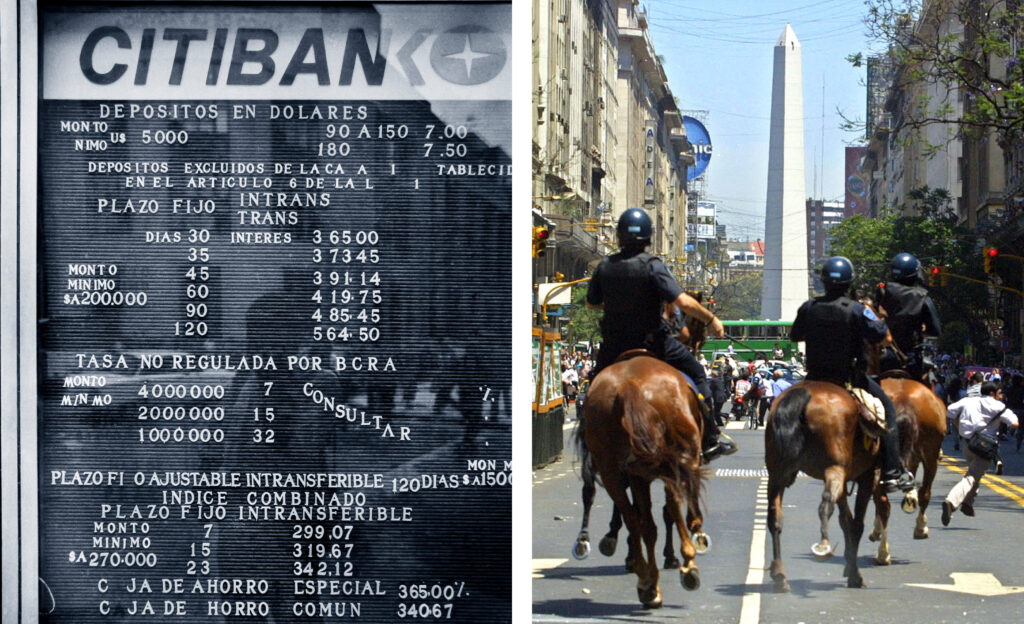

To explain: When I arrived in Buenos Aires as a reporter in 2000, the country was sinking into another one of its crises—its worst on record, in fact. Over the next four years, I would witness the biggest sovereign debt default in history, a 70% currency devaluation, and a social uprising that caused the country to have five different presidents in just two weeks.

I found all this duly shocking. But few Argentines really seemed that surprised. By that point, after all, the narrative was already well-established: This was a country that had been in sad decline for… well, how many years exactly was also a very political question. Saying that the trouble started in 1930, 1946, 1955, 1976 or 1989 was more illuminating than announcing your party affiliation. The one thing everyone agreed on was that Argentina, which was among the world’s 10 richest countries as recently as the 1930s (a phrase that must be dutifully repeated in every such conversation or political speech, it seems), had long since lost its way.

(Photos by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty and Daniel García/AFP/Getty)

I spent years digging into history books, earnestly trying to figure out who was right. There was no shortage of horrifying violence and betrayal. Soon it all started to bleed together. I wondered—I do not wish to offend with this comparison, given today’s politics—if Argentina was a bit like the Middle East. That the matter of who started it, and who was primarily to blame, was no longer the most important question, or maybe even knowable. What mattered now was the fighting itself, and the way it had led Argentines to tear apart this beautiful but delicate thing they once had. What I was witnessing in the early 2000s, as dramatic as it was, felt not like the crisis itself, but its aftermath.

Indeed, Argentina’s fall from grace, unique in modern global economic history, has produced its own self-reinforcing logic. People tend to believe that yesterday was paradise, today is hell, and tomorrow will be even worse. This pessimism confounds policymakers; one economy minister even blamed the crisis on a “depression of the state of mind.” But this behavior was not irrational, quite the contrary. Everyone in Argentina, bar the odd centenarian, has witnessed primarily stagnation and decline in their lifetimes. At the first sign of trouble, they stop investing, pull their cash out of the banks, and stuff it under their mattresses or in accounts abroad. There is a reason Argentines have an estimated $246 billion in deposits outside the country—an amount greater than half their country’s GDP. Sadly, over time, the pessimists have almost always been proven right.

Today, Javier Milei is the latest politician promising to break with this seemingly interminable cycle. “We are turning the page on this long and sad decline in Argentina … burying decades of failures,” he vowed in his inaugural speech in December. But for all the novelty Milei offers —the hair, the dogs—he is more familiar than some may appreciate. His call for Argentines to make sacrifices now, in return for better times later—“We can’t reverse a hundred years of decline from one day to the next”—sound like Carlos Menem’s assurances of “Estamos mal, pero vamos bien” in the 1990s, as some Argentine commentators have already noted. Milei’s agenda of spending cuts and shock therapy recall the so-called Rodrigazo of 1975 under Isabel Perón, Menem’s “surgery without anesthesia” or Mauricio Macri’s more timid efforts of the mid-2010s. Whether you believe those plans failed because the underlying ideology was wrong, or because they weren’t seen through to their proper completion is, again, not the central question. The important thing is that they failed, and Milei must do battle with that history.

Right: President Javier Milei after his inauguration last December.

(Photos by Jorge Duran/AFP/Getty and Marcelo Endelli/Getty)

This speaks to an additional challenge, one that has bedeviled all Argentine liberales for the last half-century. Milei says the country’s main problem today is fiscal, that Argentina’s long decline has led the country to habitually spend beyond its means, which it then finances either through borrowing or, when external sources of financing have run out, as they inevitably do, by resorting to the printing of money—which is why Argentina’s inflation is currently above 270%. Almost all mainstream economists agree, and say the only solution is austerity. But in the short run, that only deepens the prevailing negativity—it causes wages to fall, and unemployment to rise. It makes the pessimists say “Oh no, here we go again.” Patience runs out, and people take to the street, because history has taught them the promised payoff will not come—or at least, it will not last. This was the point in the cycle that Fernando de la Rúa could not get past, back when I lived in Argentina. It’s the point Milei must somehow reckon with now.

Can he do it? Is Javier Milei really the leader who will succeed where others could not, and overcome almost a century of self-fulfilling prophecies? Though it’s still early, he has done better than some expected. He has simultaneously pushed through changes to the economy, while apparently maintaining most of his popularity. This may point to a contradiction. Milei’s base is young, and seems, for whatever reason, less interested in history than previous generations of Argentines. At the same time, among all the Argentine presidents of my lifetime, Milei is the one who sounds most like the people I’ve spent 1,000 hours listening to over coffee. An economist, Milei clearly relishes the discursive references to theoretical concepts, and obscure chapters of history, that fuel so many conversations in the belle epoque confiterías of Buenos Aires. Whether knowing history makes him more likely to be its prisoner, or somehow defeat it, only time will tell.